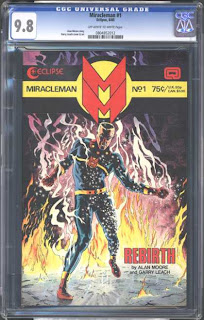

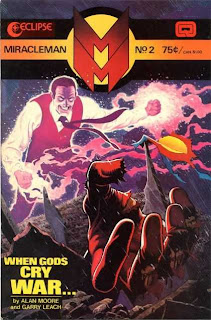

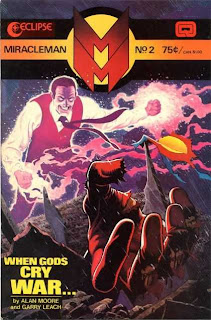

Miracleman has got to be the poster child for scheduling delays. Sixteen issues, which are the sum total of Alan Moore's run on the book, took from August 1985 until December 1989. Why, that's almost the entire 4 years I was in college, and an average of 4 isues per year for what was ostensibly a monthly book. Then again, once new material started being produced, and John Totleben was selected as the artist, it was nearly doomed to fail in keeping any production schedules.

But first, a little history. I'm sure most readers already know this, but I'll sketch it out all the same. Miracleman was originally Marvelman when he was published in the UK. In fact, he was just reprints of Captain Marvel, hero of the Fawcett Comics universe until the UK publisher lost the rights. Not wanting to give up a good cash cow, the character was slightly modified in costume and origin, but not so much so that the loyal readers would not continue to buy the books. Like Captain Marvel (DC version, not  Marvel), the lead changed from an unassuming young man (not a kid like Captain Marvel) to a nearly invulnerable superhero upon saying a majic word. Rather than Shazam, Kimota was employed. Kimota being Atomic(k) spelled backward, it fit in with the nuclear age of the 1950s. Miracleman had sidekicks Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman. His villains were largely knock offs of Captain Marvel's adversaries, with Dr Gargunza substituting for Sivana and Young Nastiman substituting for Black Adam. The Miracleman series ended in the early 1960s but was revived in the early 1980s when Alan Moore wrote new stories for Warrior magazine. These were only published in the UK but served as the first 7 issues when re-published in the US by Eclipse Comics.

Marvel), the lead changed from an unassuming young man (not a kid like Captain Marvel) to a nearly invulnerable superhero upon saying a majic word. Rather than Shazam, Kimota was employed. Kimota being Atomic(k) spelled backward, it fit in with the nuclear age of the 1950s. Miracleman had sidekicks Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman. His villains were largely knock offs of Captain Marvel's adversaries, with Dr Gargunza substituting for Sivana and Young Nastiman substituting for Black Adam. The Miracleman series ended in the early 1960s but was revived in the early 1980s when Alan Moore wrote new stories for Warrior magazine. These were only published in the UK but served as the first 7 issues when re-published in the US by Eclipse Comics.

Marvel), the lead changed from an unassuming young man (not a kid like Captain Marvel) to a nearly invulnerable superhero upon saying a majic word. Rather than Shazam, Kimota was employed. Kimota being Atomic(k) spelled backward, it fit in with the nuclear age of the 1950s. Miracleman had sidekicks Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman. His villains were largely knock offs of Captain Marvel's adversaries, with Dr Gargunza substituting for Sivana and Young Nastiman substituting for Black Adam. The Miracleman series ended in the early 1960s but was revived in the early 1980s when Alan Moore wrote new stories for Warrior magazine. These were only published in the UK but served as the first 7 issues when re-published in the US by Eclipse Comics.

Marvel), the lead changed from an unassuming young man (not a kid like Captain Marvel) to a nearly invulnerable superhero upon saying a majic word. Rather than Shazam, Kimota was employed. Kimota being Atomic(k) spelled backward, it fit in with the nuclear age of the 1950s. Miracleman had sidekicks Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman. His villains were largely knock offs of Captain Marvel's adversaries, with Dr Gargunza substituting for Sivana and Young Nastiman substituting for Black Adam. The Miracleman series ended in the early 1960s but was revived in the early 1980s when Alan Moore wrote new stories for Warrior magazine. These were only published in the UK but served as the first 7 issues when re-published in the US by Eclipse Comics.As I noted, Eclipse started publication in August 1985. It went through the first 7 issues by April 1986. Seven issues in 9 months was pretty good. It was also the best it would ever get. Issue 8 was a filler of reprinted stories from the original run of Marvelman. The reprinting was necessitated by the flooding of Eclipse's offices in California (one of several reasons not to live in CA, the other top contenders being mud slides, earthquakes, wild fires and periodic riots). Issue 9 then came out in July 1986, but monthly was a pipe dream that had gone up in smoke. Rick Veitch drew issues 9 and 10, both of which came out on the bi-monthly schedule then being proclaimed. Unfortunately, as good as John Tottleben's art was, and which started with issue 11, Tottleben suffered from an eye disorder that made it impossible to focus for fine line work. The problem was not manifest all of the time, but its manifestations were unpredictable.

That being said, Miracleman was one of the most innovative comics ever created. Moore took the moribund Captain Marvel imitator and made him not only interesting but essential to a good literary education. Seriously. Anyone educated in Western literature should make Miracleman a cornerstone in the development of myth and creative writing.

Moore first made Miracleman human. Mickey Moran was an orphan, experimented on by a secret branch of the British Air Force, as were Dickie Dauntless (Young Miracleman) and Johnny Bates (Kid Miracleman). Using alien technology discovered in a crash, clones of each were made. The clones had fantastic abilities due to their being artificially evolved to the peak of human potential. Due to fears of what the three would do with those powers, they were kept unconscious and fed a stream of dream stories of comic book battles against cartoon villains. It wasn't entirely successful, though. Gargunza was the actual scientist in charge of the project but the young men incorporated him into their dreams. Young Nastiman, as it turned out, was also an actual person. He and Miraclewoman were created by Gargunza on the side and without the knowledge of the British government. When the three test subjects came close to awakening the government agency decided they had to be destroyed. They were revived and sent to fight a alien menace that was merely a cloak for a nuclear bomb. Its detonation killed Young Miracleman, but both Miracleman and Kid Miracleman escaped. The former reverted to his base human self, Mickey Moran, while Kid Miracleman stayed in his superpowered form but lived as an average human.

Moore first made Miracleman human. Mickey Moran was an orphan, experimented on by a secret branch of the British Air Force, as were Dickie Dauntless (Young Miracleman) and Johnny Bates (Kid Miracleman). Using alien technology discovered in a crash, clones of each were made. The clones had fantastic abilities due to their being artificially evolved to the peak of human potential. Due to fears of what the three would do with those powers, they were kept unconscious and fed a stream of dream stories of comic book battles against cartoon villains. It wasn't entirely successful, though. Gargunza was the actual scientist in charge of the project but the young men incorporated him into their dreams. Young Nastiman, as it turned out, was also an actual person. He and Miraclewoman were created by Gargunza on the side and without the knowledge of the British government. When the three test subjects came close to awakening the government agency decided they had to be destroyed. They were revived and sent to fight a alien menace that was merely a cloak for a nuclear bomb. Its detonation killed Young Miracleman, but both Miracleman and Kid Miracleman escaped. The former reverted to his base human self, Mickey Moran, while Kid Miracleman stayed in his superpowered form but lived as an average human.The story picks up in 1982. Moran has no recall that he was Miracleman, but he has dreams about flying into the trap and the deaths of both Young Miracleman and Kid Miracleman, so far as he recalls. While being held as a hostage by a gang trying to steal nuclear material to sell on the black market, he sees atomic reversed in a reflection and says the word Kimota, turning him into Miracleman. He shows his wife, Liz, what has happened. He and Liz locate Johnny Bates to try to learn more, not knowing that Bates has been in Kid Miracleman form since the '60s. Eighteen years of being superior to everyone else on earth has turned Kid Miracleman into someone with total disdain for humanity, as well as a wealthy corporate honcho. Less than subtle on Moore's part, there.

In fact, I'd forgotten how much ham handed liberalism there was in Eclipse books at this time. As with Mai the Psychic Girl, we have a lot of hype about nuclear war and how bad it is that the nuclear powers have these weapons. Scout, which I'll get to in the not too distant future, envisioned a fractured US and loose nukes resulting from a Reaganesque president unwilling to relinquish the office. Let's not forget the Dictators of the World (or something like that) trading cards, which largely featured US allies. Now, as then, I'm a liberal, but this kind of thing was putting politics ahead of the story, which doesn't work whether you're writing from the left or the right.

As with Mai the Psychic Girl, we have a lot of hype about nuclear war and how bad it is that the nuclear powers have these weapons. Scout, which I'll get to in the not too distant future, envisioned a fractured US and loose nukes resulting from a Reaganesque president unwilling to relinquish the office. Let's not forget the Dictators of the World (or something like that) trading cards, which largely featured US allies. Now, as then, I'm a liberal, but this kind of thing was putting politics ahead of the story, which doesn't work whether you're writing from the left or the right.

As with Mai the Psychic Girl, we have a lot of hype about nuclear war and how bad it is that the nuclear powers have these weapons. Scout, which I'll get to in the not too distant future, envisioned a fractured US and loose nukes resulting from a Reaganesque president unwilling to relinquish the office. Let's not forget the Dictators of the World (or something like that) trading cards, which largely featured US allies. Now, as then, I'm a liberal, but this kind of thing was putting politics ahead of the story, which doesn't work whether you're writing from the left or the right.

As with Mai the Psychic Girl, we have a lot of hype about nuclear war and how bad it is that the nuclear powers have these weapons. Scout, which I'll get to in the not too distant future, envisioned a fractured US and loose nukes resulting from a Reaganesque president unwilling to relinquish the office. Let's not forget the Dictators of the World (or something like that) trading cards, which largely featured US allies. Now, as then, I'm a liberal, but this kind of thing was putting politics ahead of the story, which doesn't work whether you're writing from the left or the right.That's actually the main flaw with Miracleman. The story doesn't take the predictable superhero path, which is great. Instead we see how impossible it is for Liz to stay with Miracleman. We also see how easy it is for Miracleman to defeat any weapon thrown against him. Those sorts of things make sense in the telling of the story. A deity and a human are going to have a hard time relating. A man who can fly and is impervious to anything short of a nuclear strike is going to cause a certain amount of obsolesence for those weapons. What doesn't make sense is that Miracleman and Miraclewoman decide there's no need for any government and, by fiat, there simply isn't. Everyone has his basic needs met and is free to pursue whatever passion she wants.

How? Just saying it won't make it so. If it were that simple, we could do it ourselves. How is it that everyone has enough to eat, wear, live in? This, after all, was the main failing of communism. Just wishing everyone had the necessities to meet all basic needs doesn't magically conjure utopia. It's just a shibboleth. The many story elements Moore employs in the first 16 issues of Miracleman are wonderful, and I'll not go into all of them here. Merely creating a logical consistency to link the old Marvelman imitations of Captain Marvel to the Miracleman of 1982 is phenomenal enough, but the directions Moore took the story after that were ground breaking. But for the utopian ideal flaw, I'd say this is nearly perfect writing.

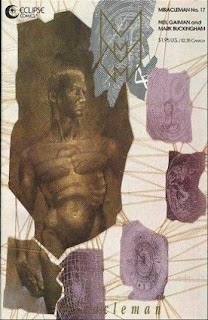

In 1990 Neil Gaiman took over the title. Issues 17-22 were The Golden Age. If the title were  taken off the covers you could easily mistake this arc for The Sandman. Dave McKean did the covers and Mark Buckingham did the interior art. The story was also straight out of Dream of the Endless. In fact, these stories, consisiting of several individual arcs that all linked together in issue 22, could as easily have been told in The Sandman without anyone noticing. There was another arc, The Silver Age, that was suppposed to run from issues 23-25, but only 23 and 24 were ever published. These featured re-created Young Miracleman and were also by Gaiman and Buckingham. I missed issue 23 and 25 never was published due to ongoing legal issues and the death of Eclipse Comics.

taken off the covers you could easily mistake this arc for The Sandman. Dave McKean did the covers and Mark Buckingham did the interior art. The story was also straight out of Dream of the Endless. In fact, these stories, consisiting of several individual arcs that all linked together in issue 22, could as easily have been told in The Sandman without anyone noticing. There was another arc, The Silver Age, that was suppposed to run from issues 23-25, but only 23 and 24 were ever published. These featured re-created Young Miracleman and were also by Gaiman and Buckingham. I missed issue 23 and 25 never was published due to ongoing legal issues and the death of Eclipse Comics.

taken off the covers you could easily mistake this arc for The Sandman. Dave McKean did the covers and Mark Buckingham did the interior art. The story was also straight out of Dream of the Endless. In fact, these stories, consisiting of several individual arcs that all linked together in issue 22, could as easily have been told in The Sandman without anyone noticing. There was another arc, The Silver Age, that was suppposed to run from issues 23-25, but only 23 and 24 were ever published. These featured re-created Young Miracleman and were also by Gaiman and Buckingham. I missed issue 23 and 25 never was published due to ongoing legal issues and the death of Eclipse Comics.

taken off the covers you could easily mistake this arc for The Sandman. Dave McKean did the covers and Mark Buckingham did the interior art. The story was also straight out of Dream of the Endless. In fact, these stories, consisiting of several individual arcs that all linked together in issue 22, could as easily have been told in The Sandman without anyone noticing. There was another arc, The Silver Age, that was suppposed to run from issues 23-25, but only 23 and 24 were ever published. These featured re-created Young Miracleman and were also by Gaiman and Buckingham. I missed issue 23 and 25 never was published due to ongoing legal issues and the death of Eclipse Comics.Seminal. Landmark. Phenomal. All good descriptions of Miracleman, especially in the Alan Moore run. Anyone who likes comics at all should read Miracleman to see how far the medium can be stretched and where the grittier, "realistic" stories of today's Marvel and DC got that push.

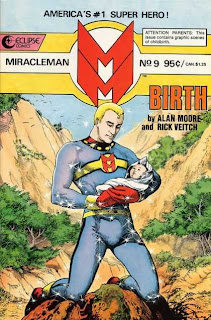

(Issue 9 has the most intimate and realistic depiction of childbirth that I've ever seen. Years later, when my own kids were born, that's just what it looked like. I'll never know why birth makes people think there's a god. If there were, and it had any affection at all for humans, it wouldn't have designed an exit that was 4 sizes too small for the occupant of the womb. Yet another imperfection in the function of the human that reinforces evolution, an inherently flawed method of development, over divine perfection.)

No comments:

Post a Comment